In the last few years, I have been reading and researching autism. It started out simple. I wondered why my partner struggled to stay focused long enough to complete a full load of dishes when I asked. Why was it a hassle? I dove into the research on ADHD and learned that neurodivergence can make easy chores, like washing dishes, feel world-ending. It was a lot to adapt to at first, but nearly 3 years later, the dishes just get done now. Then a friend asked me whether I had considered myself autistic. Well, no, considering that this was the first time it had occurred to me to think about it. I didn’t have any developmental delays or any other stereotypical signs. And then I was handed a list of testimonials and asked whether I related to any of them. As it turns out, I related to the majority of them.

I have already spoken about this on my Patreon page, so please head there if you’d like to read it in full. I felt like the only way to solve some of my life problems was to understand what autism actually is (and not my un-researched perception of it), decide whether I thought I was autistic, and what I might do about it if so. After a year of fairly intense research, looking at medical reviews of autism in adult women, testimonials, and just reflecting on frustrating interactions I had had in my life and feeling massively misunderstood, I accepted that I was probably autistic. In April 2023, I began implementing strategies to listen to my body and assess how different experiences manifested certain symptoms: extreme fatigue, weight gain, muscle and joint inflammation, anxiety, and brain fog.

After a full year of understanding myself as autistic, I can say that I have no doubt that this is the label that describes me best. I am not diagnosed but my 3 years of research is sufficient for me to say that I would receive a positive diagnosis with a professional. I would like to get diagnosed officially, but the NHS wait times are on the order of 9 months to several years and private options are pricey. Until then, I will continue living my life as an autistic person.

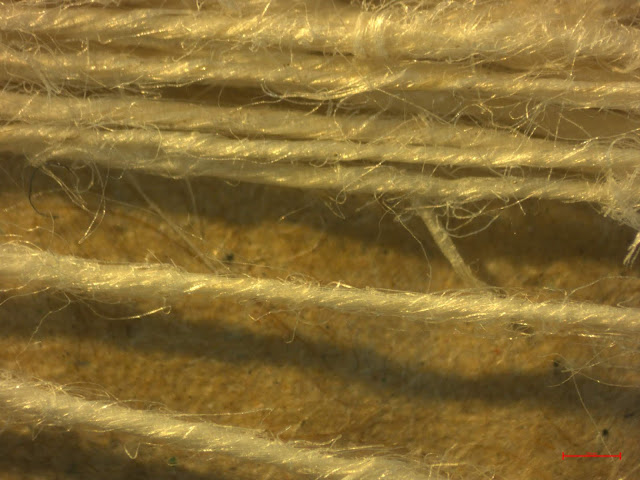

I have titled this blog entry as ‘Autistic Crafting’ for a specific reason. You may have heard me casually mention the difficulty I sometimes have when trying to make slubby art yarns. My main preference for yarns is that they’re spun consistently. I’ve been told to try spinning with my non-dominant hand (which is a fantastic idea!) so I’m a bit more loose and less controlling of the final result. However, this is something that is natural to me. In a world of chaos, autistic people tend to prefer being able to control their environment where possible. My personal obsession for perfectly even yarns likely stems from my need to form structure and order from chaos. It is how I meditate. I can spin endless miles of plain white wool into a fine yarn and be happy. I can do it while listening to the chaos around me, so long as I can make the perfect yarn.

My repeatable hand dyed yarns are another example of how autism comes into my crafting. I love the idea of randomly dyed yarn, but I can’t bring myself to just…jump into it. Even at the very start, in 2010, I had to exert total control over my dyeing method in order to feel confident that my art could be consistent. My recipes and method of dyeing are the scientific backbone of my business, but equally, it satisfies my autistic need for control over the results. And the artistry created in the resulting hand dyed yarn, well, that’s the anticipated chaos that drew me into hand dyeing yarn in the first place. I have always said I use Science to create Art, hence the brand Expertly Dyed: Art by Science. I feel a bit like I’ve come full circle in understanding myself as a crafter. My brain has been providing subtle hints over the years, but it’s only now clicked.

I could go on, and I probably will comment on autism in crafting in future updates, but for now, consider this an interesting twist to resuming blogging after 2 whole years.